Why Do We Move?

L.A. residents arrive under guard at the Santa Anita Racetrack in California before being taken to inland camps, 1942. Photo by Clem Albers/Courtesy of National Archives, photo no. 537040

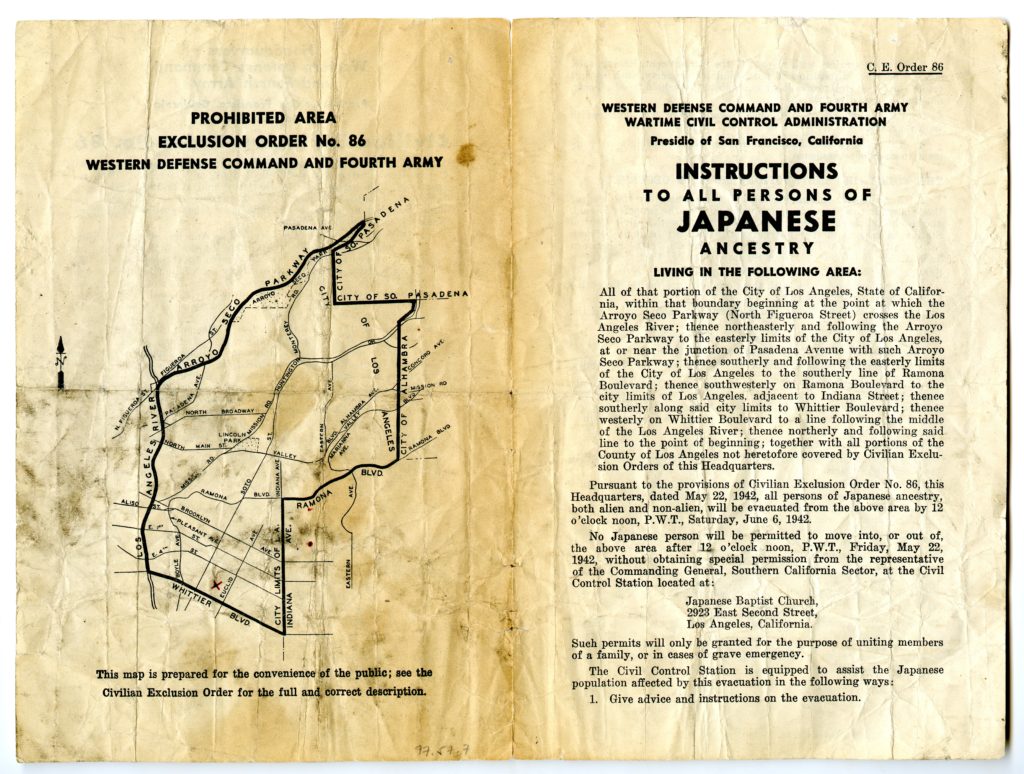

These Civilian Exclusion Order instructions were distributed and posted in East L.A. They told Japanese Americans how to prepare for their removal from the area and what they were allowed to bring with them. Japanese American National Museum (Gift of Naomi Suenaka, 97.57.7)

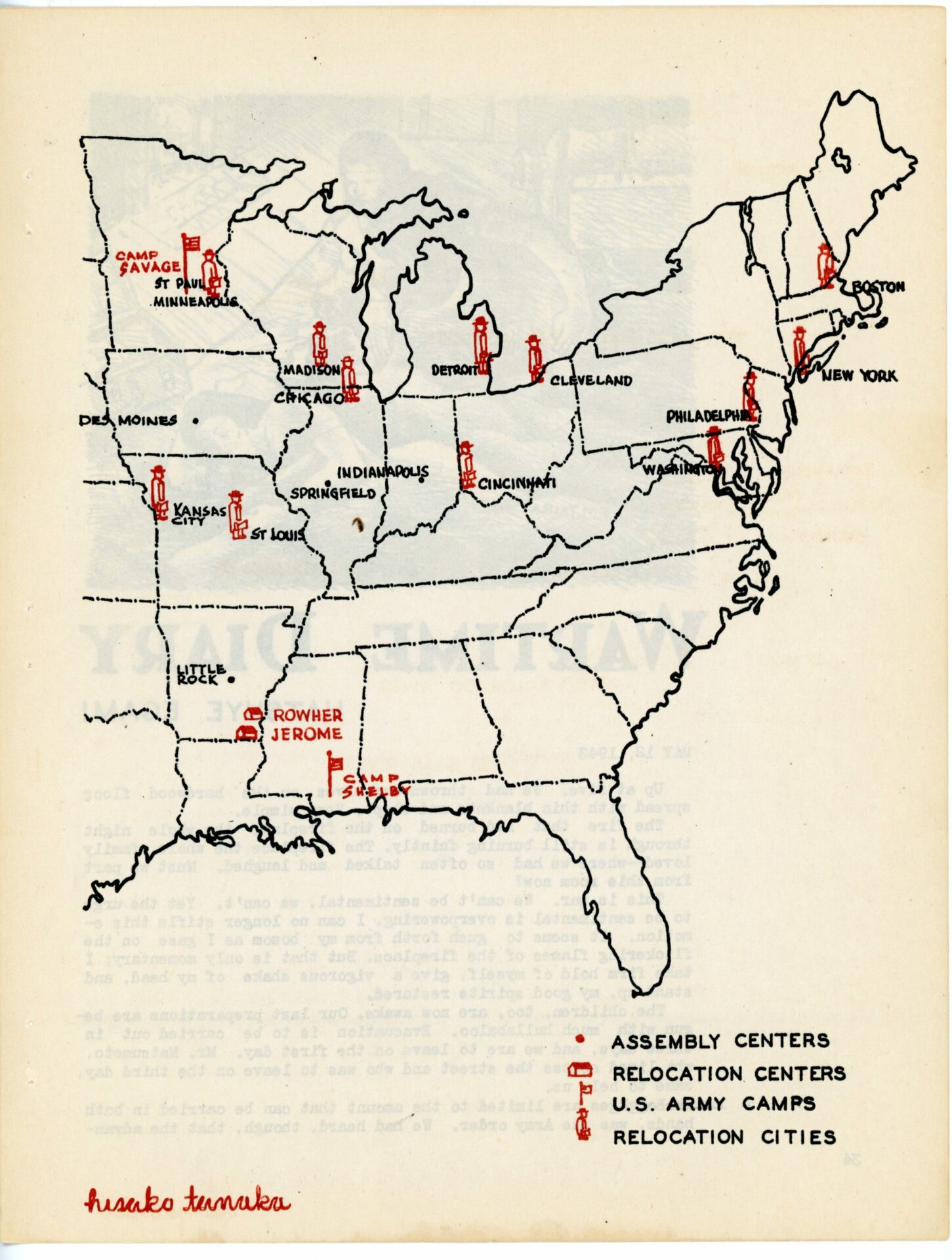

A map showing the locations of the camps across the country. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution (Division of Political and Military History)

Crossroads Stories – East L.A.

When the U.S. entered World War II, 110,000 Japanese Americans, including many East L.A. residents, were rounded up and incarcerated in inland camps. American citizens and their family members were imprisoned without due process. Wartime hysteria and racial prejudice led to entire communities being uprooted.

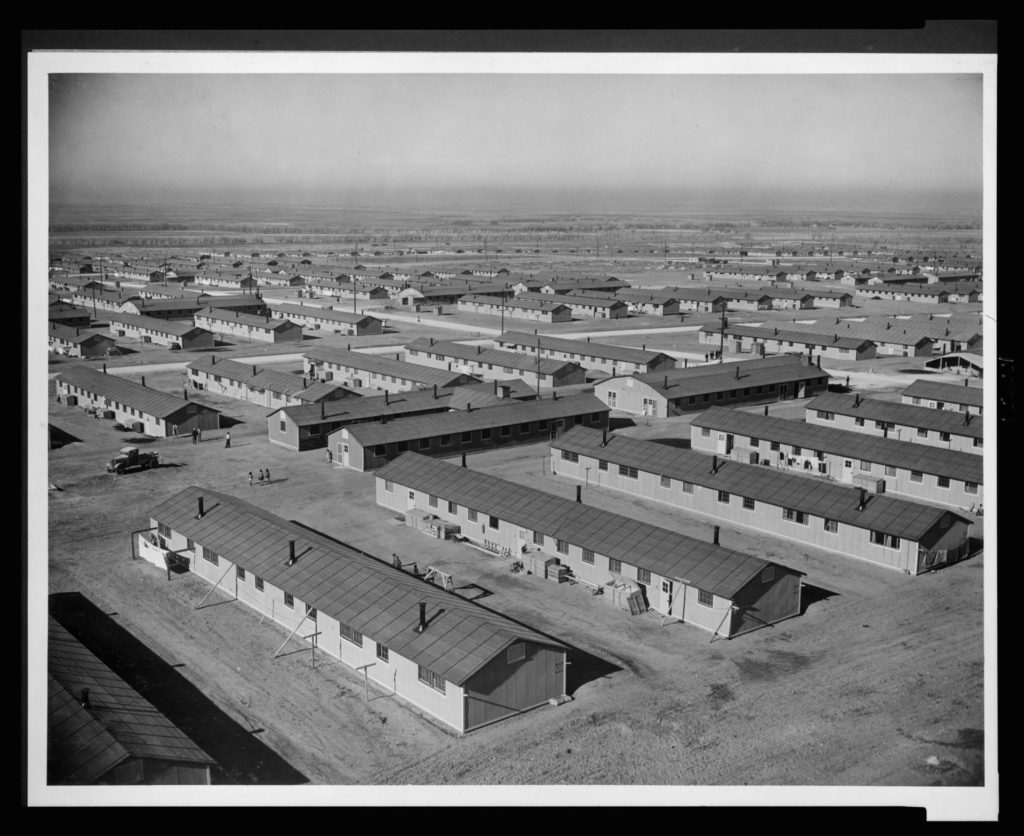

Amache camp, Colorado, ca. 1942. Photo by Tom Parker/War Relocation Authority

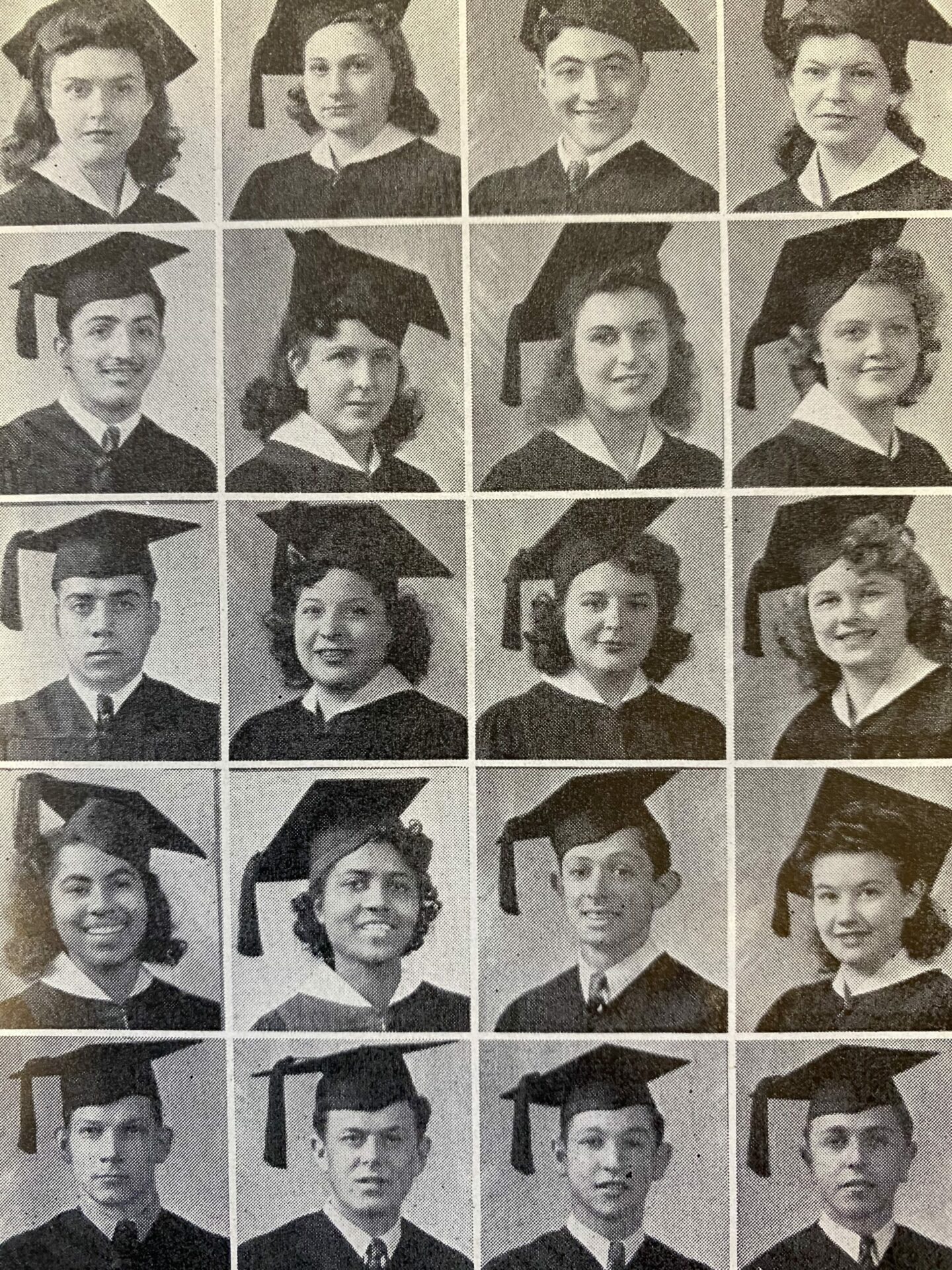

On April 9, 1942, the student newspaper shared a tribute to departing Japanese American classmates. It also reported on the efforts of Japanese American families to sell off household goods. Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Senior High School

FLIPBOOK: What was it like to be forced from home?

Explore the flipbook below to discover what life was like for Japanese American high school students from East L.A. who were incarcerated in camps across the country.

Leaving Home

Theodore Roosevelt Senior High School in the Boyle Heights neighborhood of East L.A. lost one-third of its student body during World War II. Young men left school to enlist in the military. All Japanese American students were forcibly removed with their families and incarcerated in camps.

Mollie Wilson’s Scrapbook

During World War II, East L.A. high school student Mollie Wilson kept in touch with her Japanese American friends, who were incarcerated in camps across the country.

Explore photos and letters they sent to her.

LEFT: Mollie Wilson (wearing vest) with her friend Mary Murakami; Mary Murakami (upper right); and Fujiko Murakami (lower right). Japanese American National Museum (Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy, 2000.378.2)

RIGHT: Mollie Wilson’s senior yearbook photo. Japanese American National Museum (Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy)

Keeping in Touch

Roosevelt High School senior Mollie Wilson sent care packages and letters to dozens of her Japanese American friends.

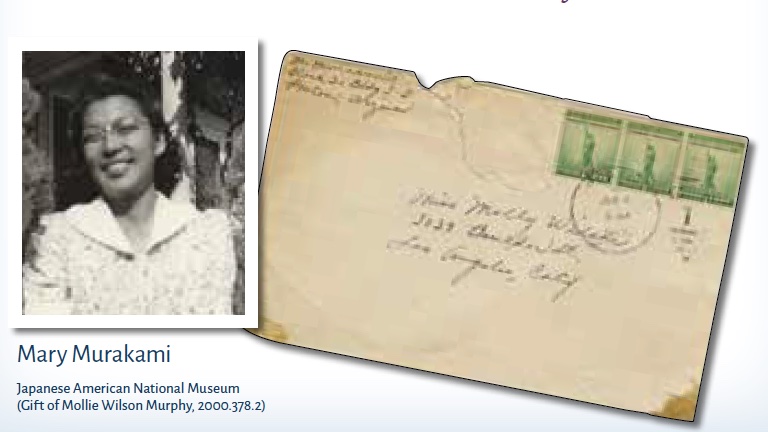

Mary Murakami Japanese American National Museum (Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy, 2000.378.2)

‘There’s no place like home’

Mary Murakami sent Mollie a letter as soon as her family had settled into their barracks at the Poston camp in Parker, Arizona. She describes the journey, their arrival, the lack of privacy in the latrines, and the blazing heat of the desert.

“. . . there’s no place like home. You realize the value of all the things you leave behind. Including bath. We do our washing by hand, and what a job! Everything is muddy. My hair is even muddy. . . And my face is all sun burned.”

—Mary Murakami

Sandie Saito sent Mollie Wilson this signed photo of her wearing their high school letter sweater. Japanese American National Museum (Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy)

‘Prisoners of war’

Mollie’s friend Sandie Saito sent a letter describing her family’s initial confinement in an “assembly center” at the Santa Anita Racetrack northeast of L.A. After a few months, Sandie and her family were moved to the Granada camp (also known as Amache) in Colorado.

“They’re getting strict here too! They don’t ever let you bring a bar of candy in the camp. The soldiers take it away. When someone comes to visit you at the gate you have to talk real loud because they don’t let you get close to them. . . . They sure think we’re prisoners of war.”

—Sandie Saito

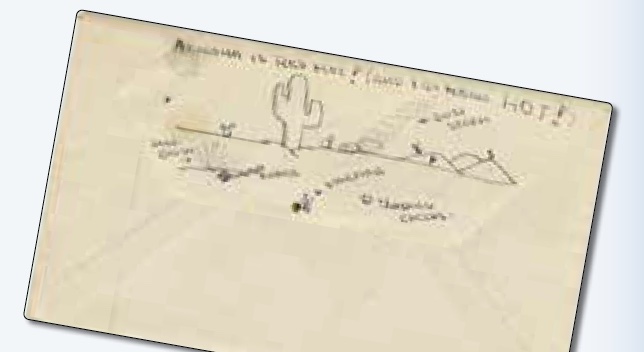

Envelope art by June Yoshigai from a letter she sent to Mollie Wilson while June’s family was incarcerated in the Gila River camp in Arizona. Japanese American National Museum (Gift of Mollie Wilson Murphy, 2000.378.16A)

‘Scattered throughout the United States’

Although they were not permitted to return to the West Coast, Japanese American students who met specific requirements were allowed to leave the camps to work or attend school. In 1944, after resettling in Ohio for school, Sandie Saito sent Mollie the whereabouts of their neighborhood friends, now “scattered throughout the United States.” After the war, Sandie stayed with Mollie until her family was able to reestablish a home in Los Angeles.

‘I don’t know how things will turn out’

June Yoshigai wrote Mollie a letter sprinkled with Japanese-language terms in January 1945 after the West Coast began permitting Japanese Americans to return. June and her family had been incarcerated at the Gila River camp in Arizona. She wrote this letter from Illinois, where she was attending college.

“The West Coast is now ‘opened’ to us—it seems so strange. Well Molly, I don’t know how things will turn out. Eventually, I suppose, we’ll return to Los Angeles, but I’m “planning” to stay here for awhile. . . . Here in Illinois—the opportunities are much better—more jobs available (at present, anyway), the people, as a whole—appear to be more fair in their judgement, and broad minded.”

—June Yoshigai

Continuing Friendships

After World War II, some of Mollie’s friends returned to Los Angeles. Others resumed their lives elsewhere. Mollie graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles; became a Spanish teacher; and started a family of her own. She remained friends with her Japanese American classmates long after World War II.

Syrian and Iraqi refugees arrive in Lesvos, Greece, from Turkey. Those who make it to the island are often fleeing poverty and violence and face an uncertain future. Photo by Ggia via Creative Commons

Volunteers guide a refugee boat to shore in Lesvos, Greece. Photo by Malcolm P Chapman/Shutterstock.com

Crossroads story – Mediterranean

The Greek island of Lesvos is just six miles from the Turkish coast. In recent years, it has been a destination for hundreds of thousands of refugees and asylum seekers from conflict-torn parts of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa. The island has witnessed dramatic arrivals, heart-wrenching deaths at sea, and a massive influx of humanitarian assistance.